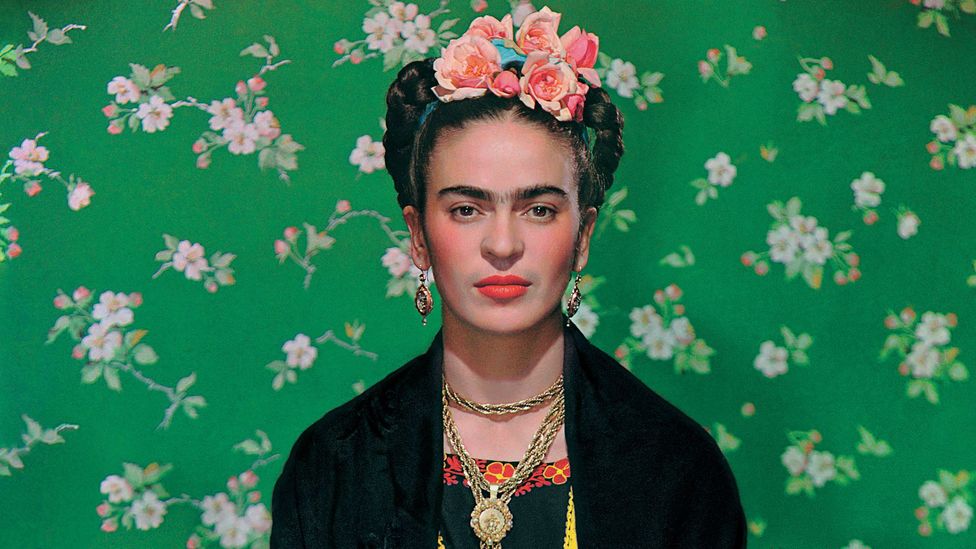

Frida Kahlo: A Deeper Dive

I’ll admit, before researching Frida Khalo for this blog post today, I really didn’t know much about her except that she was a successful painter with a pretty cool unibrow. However, from what I gathered, she had a pretty messy life. Her journey as an artist started after a bus accident which left her bedridden in a hospital, and it was there she first started painting. These paintings consisted mostly of eccentric self portraits which encapsulated the pain and suffering she felt at the time. Throughout her tumultuous life, she married two Mexican artists, had many affairs, and suffered from numerous health complications, including a miscarriage. However, what I find most fascinating about Kahlo is her interest in politics. As she gained popularity posthumously, the political nature of her work became erased, and her personal style was instead emphasized. Her artwork has often been interpreted as something similar to a personal diary: a vivid expression of her emotions which often were reflections of the hardships she experienced. However, as art historian Janice Helland writes, “As a result, Kahlo’s works have been exhaustively psychoanalyzed and thereby whitewashed of their bloody, brutal, and overtly political content.” Her politics were an important part of her life, and that was reflected onto her artwork.

Kahlo joined the communist party in the 1920s and remained involved in anti-imperialist politics her whole life. She grew up in an environment heavily influenced by the Mexcian Revolution, and she took much inspiration from the resurgence of national pride and the spread of progressive ideas that followed. She moved to the U.S. in 1930, and became very homesick and unhappy. On a political level, this period of time caused her to become very critical of the country, which she viewed as the embodiment of the exploitative nature of capitalism and the oppression of the working class. Many of her artworks clearly depict political messages, such as a painting she completed in her final days, Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick. In this work, Kahlo depicts Marx as a god-like entity who is taking revenge on the unjust forces of capitalism and imperialism and about to bring her to heaven. She remains topless, showing the leather corset that had been supporting her broken back since the bus accident and appears without crutches. And perhaps the most fascinating part of the artwork, where others would have held onto a bible in their final moments, she is depicted grasping instead a little red book—the Communist Manifesto. However, this aspect of her art is often stripped away by the contemporary exhibits dedicated to her. Acknowledging that part of Kahlo while celebrating her work would disrupt the dominant discourse and allow those ideas, too “radical” for many, to be imposed on our conformist Western middle-class values and psychology.

By ignoring this aspect of her life, we strip her artwork of its intended meaning. Communist, feminist, nationalist– all these words describe not only Kahlo’s political views but also her career as an artist. As Helland notes, “since she was a political person, we should expect to find her politics reflected in her art.”